Indaziflam Use in Boulder County Questions — Asked & Answered

On January 21, 2026, Boulder County Commissioners Levy and Loachamin voted 2-to-1 to lift the December moratorium and move forward with aerial broadcast spraying of indaziflam and other chemicals on Red Hill open space, near DAR, Yellow Barn, and many other farms, schools, and private property.

In Person Action

You can register to testify in person or via Zoom at any of the regularly scheduled public meetings of the Commissioners. This issue does not have to be on the agenda for you to speak up about it, and the more they hear directly from their constituents, the better. Public meeting schedule is online.

Virtual Action

You can write to the Commissioners and Parks and Open Space Advisory Committee (POSAC) and make your voice heard. Emails to POSAC become part of public record and this type of engagement is necessary for policy change to happen.

Ashley Stolzmann— astolzmann@bouldercounty.gov

Marta Loachamin— mloachamin@bouldercounty.gov

Claire Levy— clevy@bouldercounty.gov

POSAC— posinfo@bouldercounty.gov

Action Opportunity

Background & Context

Boulder County’s public open space lands have been used as “ground zero” to test Bayer/Envu’s herbicide indaziflam’s ability to eradicate cheatgrass and other annual grasses since at least 2019. In response to pressure from community members, our County’s Integrated Weed Management Plan was updated in late 2024 for the first time in over 20 years. While aerial spraying of herbicides by plane was banned—along with the use of 2-4,D, Dicamba, Glyphosate, and several other chemicals—County staff have proposed significantly increasing the areas sprayed with indaziflam—both manually and through aerial drones—with the stated objective of increasing biodiversity by eradicating the exotic annual species cheatgrass–a plant that has been in Colorado since at least 1892.

The recently passed Weed Management plan calls for spraying 3,000 acres in our County foothill properties over the next 4-5 years starting with a plan to conduct drone-based applications in an area just west of highway 36 in the Heil Ranch/Red Hills area that was supposed to start in early December 2025.

In late December 2025, two of our three County Commissioners–Marta Loachamin and Ashley Stolzmann responded to over 1,000 community members and took the courageous step to push back against the Staff’s plan and called for a temporary halt to the use of drones to spray indaziflam across hundreds of acres. However, the halt was only temporary, and on January 21, 2026 the moratorium was reversed, meaning that aerial broadcast spraying of indaziflam will likely resume any day now if there isn’t a sustained demand by the community to take a different approach.

This unnecessary use of untested biocides needs to change—now—not in 2027 when the Weed Management Plan is next up for review.

We are asking the County to:

Enact a moratorium on all use of indaziflam on our public lands throughout 2026;

Restore transparency and full disclosure of all relevant information and data on past, present, and planned use of indaziflam;

Create a more rigorous and transparent review process;

Conduct multi-year non-chemical control pilot projects to control cheatgrass.

What Is Indaziflam and Why Are We Concerned About This Chemical In Particular?

Indaziflam is referred to technically as a “preemergent” herbicide, which means it is designed to kill the seeds of plants as they start to germinate, before they emerge from the soil. It was developed by the German chemical giant Bayer (which has since merged with Monsanto) and the specific indaziflam products being applied in Boulder County, called Rejuvra and Esplanade, are now owned by a spin-off company of Bayer called Envu. Indaziflam’s main ‘claim to fame’ is its long-lasting effectiveness—it remains lethal in the seed bank for years after just one application. To be effective in preventing “weed” seeds from sprouting, indaziflam was designed to bind to soil molecules in ways that keep it in the seed bank, killing the majority of seeds—exotic or native—for years after just one application. Boulder County staff recently published findings that suggested indaziflam’s lethal effects could last up to 8 years, but no one really knows how long its impacts remain in the soil.

As many people now realize under the current administration’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—the agency that approves new pesticides for use, indaziflam’s “non-target” impacts—meaning any impact the chemical has on any living organism other than than the one it’s marketed to kill—have not been sufficiently studied to warrant its broad application on our Open Space lands. In fact, indaziflam received only a accelerated “conditional approval” from the EPA that circumvented more rigorous analysis of many non-target impacts when it originally came to market.

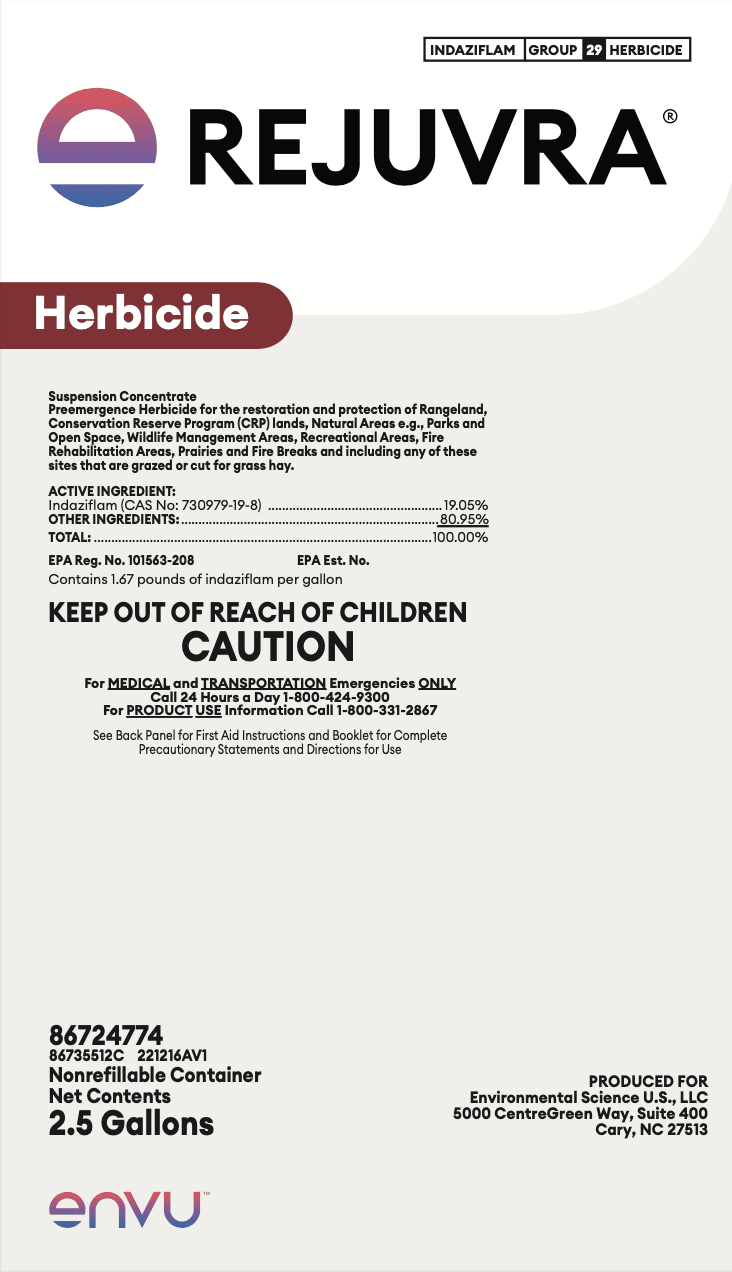

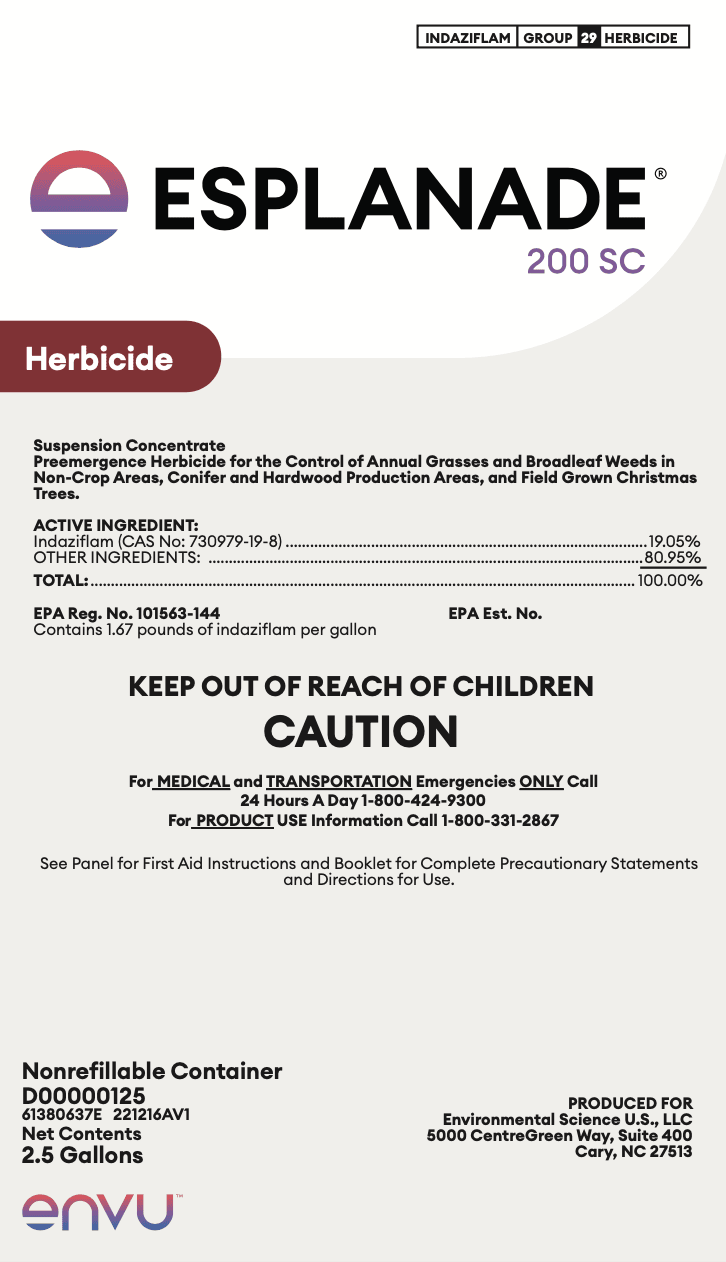

All you have to do is read the official product labels for Rejuvra and Esplanade and consider their persistence in the environment to know that we should not be applying this toxic chemical to our natural and working public lands. The impacts of these chemicals on our native seed bank and their known toxicity to aquatic life—as well as everything we don’t know about their impacts on non-target species, such as soil microbial life, mammals, birds, and invertebrates—should be enough to merit further testing and research before wide applications.

Why Is This Coming To A Head Now?

Boulder County announced in a press release on November 21st that they plan to use drones to spray both indaziflam (brand name Rejuvra) and imazapic (brand name Plateau) to kill invasive annual grasses (cheatgrass) throughout the Red Hill Open Space area—which is uphill and immediately adjacent to both Yellow Barn Farm and Drylands Agroecology Research’s (DAR) Elk Run Farm—starting as soon as this December 1, 2025. These farms have both been outstanding leaders in healing our County’s soil for many years, and exposure to the drift, run-off, and long-term seed-killing effects of Indaziflam would be devastating to these farms.

DAR, Yellow Barn, local farmers, numerous community groups, environmental groups, and many neighbors adjacent to Heil Ranch, Red Hill, and nearby areas mobilized and sent the County Commissioners around 1,000 emails over the course of a week, demanding that the spray be halted.

The Commissioners heard public testimony during an open comment period and then held a follow-up meeting on December 9, 2025 at which time Boulder County Commissioners Stolzmann and Loachamin voted 2-to-1 to postpone planned drone spraying of indaziflam at Red Hill open space.

This webpage has been created to refute incorrect and incomplete claims made by Boulder County Open Space Staff and Commissioner Claire Levy regarding the need for and safety of Indaziflam on our public lands.

Doesn’t the County have to use indaziflam to control cheatgrass?

Land managers, particularly those responsible for controlling invasive weeds face many significant challenges. Years of unwise management practices that have disrupted and degraded lands have caused many properties to lose the biodiversity and resilience that maintain healthy ecosystems. These degraded lands are susceptible to occupation by non-native “weed” species that are considered undesirable or that can displace native species.

Some of these “exotic species” are so effective at displacing or excluding reestablishment of native or otherwise desirable species (agriculturists often want other exotic species that are prized for their agricultural value e.g. alflalfa, wheat, various non-native hay crop grasses) that they have been mandated for removal by the State. These “List A” species require that local land managers take actions to remove them. With other factors like climate change and increasing arrivals of exotic species from our globalizing world, this means our public land managers have an increasing workload in trying to manage for the removal of these species.

Beyond these species that are mandated for removal, there are a larger lists of species (Lists B and C, and watch lists) that are targeted for “containment” (stop the spread), and naturalized exotic species that are well established and may simply be a preference for removal or control (List C). Only List A species have mandates for land managers to try and remove them.

To recap, County staff are not required by the state or any other authority to control cheatgrass. Cheatgrass has been documented in Colorado since 1892 and is a Class C Noxious weed. Class C weeds are recognized by the state’s noxious weed guidelines as being impossible to eradicate because they have become so ubiquitous. Local entities like the county have an option to create their own management plans for class C species, but they are in no way obligated to.

Nevertheless, with limited budgets and human resources, many weed managers are impressed with indaziflam because it is significantly more effective at controlling annual invasive grasses, such as cheatgrass, than other herbicides. A recent study published by Boulder County weed management staff showed that indaziflam—when applied with glyphosate—controlled cheatgrass for up to 8 years (they did not study the long-term impacts of indaziflam alone).

Ok, maybe cheatgrass doesn’t legally have to be controlled, but doesn’t indaziflam restore biodiversity and benefit native plant communities?

Before we get into the impacts of indaziflam on native plant communities, we need to establish whether or not cheatgrass is the existential threat to biodiversity in Boulder County that some land managers claim it is.

While there is no doubt that non-native species contribute to major upheavals in biodiversity worldwide, before we contaminate our public lands with a toxic chemical designed to be persistent for up to 8 years that suppresses native seed germination, it is incumbent upon us to truly understand the problem before applying herbicides.

The County has asserted that removing cheatgrass is essential to protect numerous areas of unique biodiversity like the Red Hills area slated for drone spraying of indaziflam in December 2025, but there are numerous problems with this assertion.

First, cheatgrass is not a new arrival to our area. Its first recorded presence in this area is in 1892. It became established in large part due to patterns of overgrazing that accompanied the arrival of dispersed grazing that started in the late 1800s. Cheatgrass flourishes in areas that are degraded. It is now largely “naturalized” in our area. Recent research conducted by CU Professor Emeritus Tim Seastedt has found that in many areas around Boulder County where we are restoring with more ecologically-based management systems, cheatgrass is actually in retreat. This research was provided to the County as part of the 2023 Weed Management Plan update.

The bottom line: there is no major cheatgrass “invasion” taking place. It’s one of the reasons why cheatgrass is a “List C” invasive species—not considered a high priority for treatment by the State. If the County believes there are significant threats to biodiversity being created by this species that has been in the area for over 100 years, it needs to provide scientifically rigorous data that proves this assertion, not merely “staff observations.”

Nevertheless, “suppressing” cheatgrass has become a priority alongside the availability of Bayer (now Envu’s) new indaziflam-based products, Rejuvra and Esplanade. So what do these companies claim about their products, and is it true?

Bayer/Envu and their spokespeople assert that indaziflam controls cheatgrass, thus “releasing” native plants and restoring native plant communities.

Indaziflam does control cheatgrass–and any other annual plant that grows from seeds each year–exotic or native. In areas with established perennial plants (both native and non-native), the perennials that are already present will tend to grow and expand after indaziflam treatment due to having less competition from annual plants, including annual native plants. In highly diverse native plant communities with lower cheatgrass density, there may be a slight improvement in native plant diversity versus cheatgrass, due in part from cheatgrass being removed from the system. Proponents of indaziflam frequently show before and after pictures or take people on tours to show perennial native plants in areas where the removal of cheatgrass has resulted in more vigorous growth of perennial native plants.

However, almost all of the study and documentation of indaziflam have looked at this above-ground dynamics—not soil health or the seed bank. This is why there is the frequently repeated statement that “indaziflam benefits native species”. Again, this may be true in the short term for those perennial plants that are already established, but the problem with this approach is it’s not looking at the zone of activity indaziflam was designed to be lethal in—the soil and the seed bank.

As more studies are now starting to look at the below ground and scientifically measure seed bank impacts, we are starting to get a very different picture of indaziflam’s potential long-term impacts. In both recent published studies and in analysis presented during the Society for Ecological Restoration’s 2025 conference on indaziflam’s effects on the soil and seed bank, we now know that indaziflam kills not just exotic annual grasses, like cheatgrass, it also kills native plant seeds. As far as we know, no longer term studies or modeling have been done on what the long-term ecological impacts of this seed bank depletion could do to the health and resilience of the thousands of acres the County and other land management agencies are now applying indaziflam to. Especially for fire-prone areas like ours, protecting the seed bank should be an absolute priority and requirement.

Doesn’t indaziflam only target invasive plant species like cheatgrass?

County staff have stated that indaziflam only targets cheatgrass, or “invasive annual weeds.” This is simply false. Indaziflam is non-selective, meaning that it kills the seeds of grasses, forbs (flowers), annuals, biennials and perennials—both native and non-native. Seeds from the vast majority of plant species are suppressed for years after one indaziflam application, although a few plant species—both invasive and native—appear to be somewhat tolerant (see Rejuvra pesticide label for list).

Finally, people should not be led to believe that killing annual weed seeds enables perennials to thrive and “recover.” Perennial plants come back in the spring because their root system has overwintered, but in order to reproduce and grow their population, they need to produce seeds! Many of these native species have evolved to produce far more seed than would ever sprout in a year specifically to build up a seed bank that is adapted to come back after fires, floods, or whenever “the stars align.” These presence of healthy native seed banks are the reason why we get some wildflower superbloom years where it seemed like fewer plants existed before.

Ok, maybe indaziflam is actually a danger to native plants over the long term, but I’m still worried about fire. Don’t we need to use herbicides to reduce dry grasses that are a fire risk?

Fire risk and recovery is such an important topic for our community; one that demands complex critical thinking from all of us.

There are issues around cheatgrass and fire risk to be considered, but there are also issues of post-fire restoration, and the topsoil loss that is such a massive challenge in a post-fire landscape denuded of plants and vulnerable to erosion by wind and/or water.

County land managers have stated that using indaziflam to suppress cheatgrass will make us safer in a landscape that evolved with grassfires.

This echoes indaziflam manufacturer marketing claims, which have attempted to take advantage of the legitimate and growing concerns over catastrophic wildfire risk across the world by asserting that use of indaziflam can reduce this risk because it can reduce or eliminate cheatgrass. This argument assumes that cheatgrass is a major vector for spreading wildfire, and they point to one study in the Great Basin in Nevada as evidence of this connection. We have a very different ecosystem here than they do in Nevada, and cheatgrass/fire dynamics are not the same here.

As anyone who has walked through the hills along the highway 36 corridor that is proposed for drone spaying knows, these are highly varied landscapes that include a wide diversity of plant communities. While there are some areas that have high densities of cheatgrass, many areas are dominated by both native grasses and forbes. These native species also become dry and are prospective fuel sources in later summer and fall. Cheatgrass is in fact much less robust as a fuel source than many of these other taller and more robust native species (cheatgrass grows very low to the ground with fine stems with very limited fuel content).

It must be acknowledged that given what we are now seeing with regard to indaziflam’s destruction of the native seed bank, it’s quite possible that use of indaziflam could be one of the worst things we could do in relation to fire. Imagine a fire taking place that destroys the vegetative cover of an area that has been recently treated with indaziflam. Without viable seeds to sprout and establish root systems that can stabilize the soil, we could have severely damaged our soils, which would then quickly be lost to wind and water erosion, potentially creating unrecoverable landscapes—sometimes called moonscapes—largely devoid of any life.

If the County wants to assert that this single species is the primary risk to the spread of fire, it needs to produce independent science-based analyses conducted in our landscape that prove this association. We shouldn’t be spreading poisons that will kill our native plant seed bank based on an unsubstantiated assertion that killing one scattered species will somehow make us safer.

Ok, so the need for indaziflam and the broader ecological impacts are in question, but at least we know it’s safe as long as we “follow the label”…right?

Actually, the EPA’s approval process, during which product labels are created, in no way guarantee the safety of any living creature exposed to these chemicals. The label outlines precautions applicators are legally obligated to follow to minimize exposure. Furthermore, it would be next to impossible to even follow the label for these products in the areas where staff are already using them (and have proposed to expand use). For example, Rejuvra’s label states:

• DO NOT allow spray drift or runoff to fall into irrigation ditches.

• Do not apply in situations where the soil can be easily washed, blown, or moved onto cropland or land containing desirable vegetation.

• Applications made to areas where runoff water flows onto agricultural land may injure crops.

• Treated soil should be left undisturbed to reduce the potential for Rejuvra® movement by soil erosion, by wind, or water.

• Applications should be made only when there is little or no risk of spray drift or movement of applied product into sensitive areas. Sensitive areas are defined as bodies of water (ponds, lakes, rivers, and streams), habitats of endangered species, and non-labeled agricultural crop areas.

The above restrictions alone would disqualify many areas staff has already sprayed or plans to spray. Staff has also made the following assertions, which have significant untruths that must be rectified.

ASSERTION #1: Indaziflam has been assessed by the World Health Organization and deemed a low-hazard herbicide.

County staff testified to the Commissioners in public meetings in December 2025 that indaziflam is a low-risk choice for staff which had been “assessed to be safe” by the WHO and listed as a low-hazard herbicide by the World Health Organization (WHO) on its “Table 4.” This is completely untrue. The current Boulder County Integrated Weed Management Plan, in Appendix D (page 54) links to the The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification document, which was published in 2019. The WHO document does not even mention indaziflam, and indaziflam does not appear on Table 4—go to page 48 to see for yourself.

To reiterate, indaziflam has not been “approved” or deemed low-risk by the WHO, therefore, Boulder County's claim that they are using "WHO standards" to approve indaziflam is unsupported. Additionally, indaziflam is not allowed in all 27 member States of the European Union and is also banned in the UK.

ASSERTION #2: The County has had a three-person expert panel review indaziflam’s safety.

On page 53 of the Integrated Weed Management Plan, the County states: “For any active ingredient that has not been evaluated by the WHO, Boulder County contracts out an evaluation to be done following the WHO guidelines. If the evaluation places the active ingredient on Table 4 or Table 5, it is approved for use. “

Presumably, this is why we just learned from staff testimony to the Commissioners in December 2025 that staff had invoked this clause to convene a 3-person review panel for indaziflam. The timing, content, and composition of this panel are problematic and this lack of transparency and seeming rigor needs to be addressed.

Re-Timing—County staff recently revealed for the first time in late December 2025 that they had invoked a provision of the newly approved 2024 weed management plan in which they created a 3-person panel to review indaziflam, however, they have been applying indaziflam to our public lands since at least 2019, years before this plan or that panel were ever created. So, if the approval was legitimate, it was retroactive at best.

Re-Rigor—The public, and likely County Commissioners and POSAC, do not know what questions the panel members were asked to consider or if they considered any of the issues raised above. This review lacks both the credibility and transparency we would expect from the potential application of a powerful toxic chemical across hundreds of acres of our public lands–many of which are adjacent to residences and farms.

Re-Composition—This 3-person panel included a pesticide application safety specialist (not a public health specialist), an entomologist who had recently received her PhD from Cornell, but whose experience is entirely in eastern US and tropical landscapes, and an agricultural weed management specialist from Kansas State whose biography states that her focus is on “managing herbicide-resistent weeds which are a major threat to sustainable crop production.” The group lacked individuals with a background in environmental toxicology, local rangeland ecological conditions, or local land management practices. The public has seen no documentation of the review this panel conducted, and that should be made available.

ASSERTION #3: EPA has reviewed and approved the safety of this chemical

The County’s weed management plan also asserts that indaziflam should be considered safe for use because it is approved by the EPA. There are a number of reasons why this assertion should be actively disputed.

The EPA has approved indaziflam under an accelerated conditional use procedure that circumvented more extensive non-target impact assessment. All of the testing used to assess and approve indaziflam was provided by Bayer Crop Sciences. Check out this EPA fact sheet and the over 75 pages of exclusively Bayer Crop Science tests used for the registration of indaziflam. (see: EPA Indaziflam Fact Sheet). There is a clear lack of unbiased, independent assessments of indaziflam’s safety or non-target impacts in the EPA’s approval process. These registration tests are not peer-reviewed and are, in fact, not even available for scrutiny since they is considered confidential business information.

The EPA label for this product lists multiple serious risks including:

Environmental persistence

Potential groundwater contamination

Neurotoxicity

Endocrine disruption

Non-target species toxicity

The assertion that indaziflam is a low-risk chemical isn’t even supported by the product’s own label—click the label images below to download the labels and read them yourself. Both of these products feature indaziflam as their active ingredient.

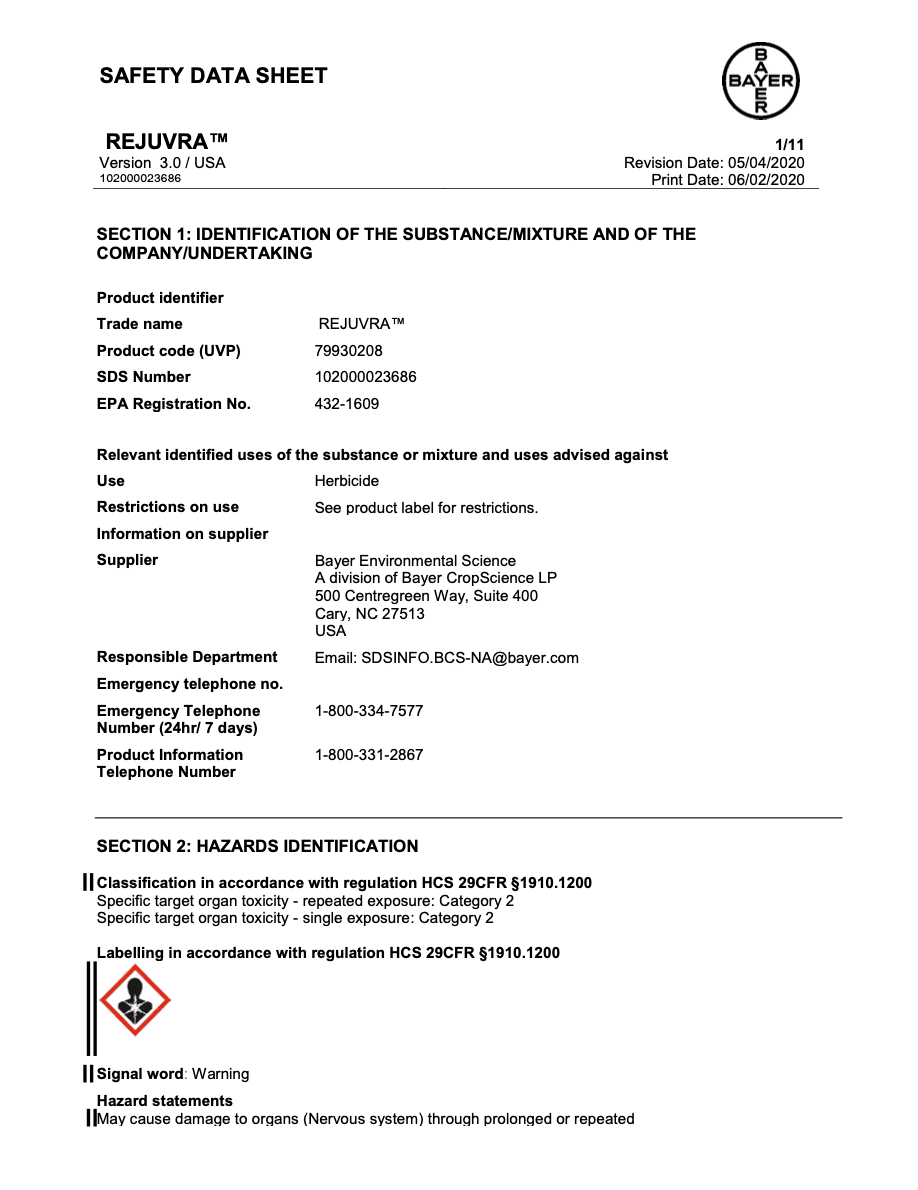

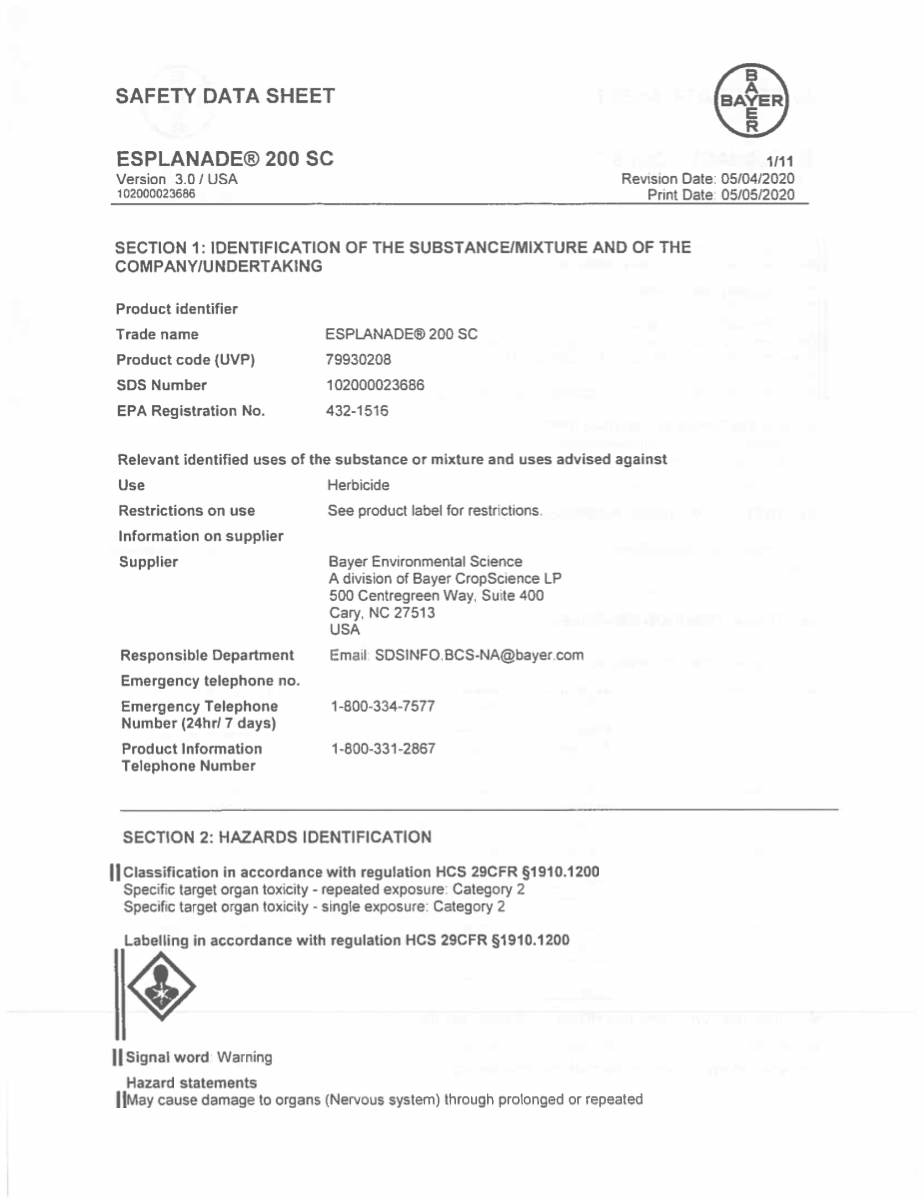

Click on the images below to download the “SDS” or Safety Data Sheets (previously called Material Safety Data Sheets MSDS) for the indaziflam products Boulder County is using on our open space lands. SDS’s provide information on substance hazards, safe handling, emergency procedures, storage, environmental impacts, PPE requirements, etc. The format and symbols of these sheets have been globally standardized in something called the Globally Harmonized System (GHS).

These are required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for all hazardous chemicals in the workplace; so OSHA requires that they are provided to customers by manufacturers and that employers have them readily available for all employees on the job who are coming into contact with these chemicals. The manufacturer is the party responsible for authoring these documents based on the best available scientific data, but sometimes they will hire contractors to author for them.

Pesticide labels are required by the EPA, and include product ingredients, brief safety and first-aid info, and application instructions. These are provided by the manufacturer based on their own scientific data and are approved by the EPA (an often-rushed process due to the number of new products submitted each year).

The largest differences between product labels and SDSs are:

SDS sheets are more comprehensive than pesticide labels in the information that they provide and are the gold standard for toxicological and safety information

SDS sheets are required and enforced for accuracy and standards by OSHA; pesticide labels are required and enforced by the EPA

The info on SDS sheets could come from other sources besides the manufacturer; the info on pesticide labels almost always comes from research conducted by the manufacturer themselves.

Furthermore—and this is such an important point that is often obfuscated in discussions about herbicide use—EPA approval does not even evaluate much less guarantee a product’s safety–what they look at is a product’s efficacy; how well does it kill what it’s supposed to kill? And then they try to minimize liability for the known safety hazards by listing “appropriate use” conditions on the label. Examples of the EPA approving chemicals that are later proven by independent scientists to be extreme human health hazards abound. Here are just a few examples of EPA-approved chemicals that are known to cause cancer, neurological and reproductive harm, or other “non-target impacts.”

Atrazine–The EPA still allows atrazine, the 2nd most commonly used herbicide in the US, despite it now being known to be associated with Parkinsons, is a significant carcinogen, endocrine disrupter, and the cause of serious reproductive issues as well as urogenital birth defects in baby boys. 31 other countries now ban its use, including all of the EU.

Paraquat–The EPA still allows this chemical which is now clearly linked to Parkinsons disease.

2,4-D and Dicamba–both of these chemicals are approved by EPA and were previously on Boulder County’s approved list until there were over 3,000 people in the County that spoke up during the Weed Management Plan update in 2023 and demanded a change. Both of these chemicals were then removed from the County’s approved list, because when we know better, we should do better.

Glyphosate (Roundup)—Finally, glyphosate—commonly marketed as “Roundup” continues to be approved by the EPA despite thousands of lawsuits from cancer patients poisoned by glyphsate and recent revelations that the supposedly independent peer-reviewed science used to justify the chemcial’s safety, which was used in its EPA approval process, was literally ghostwritten by the product’s manufacturer–Monsanto (now Bayer). The journal Science, in which the primary safety research had been published, publicly withdrew the paper late last year.

Do we really believe, particularly at a time in which even the existing oversight infrastructures of agencies like the EPA are being dismantled, that we can trust the findings of the EPA when they are clearly dependent on the very companies they are supposed to be regulating for the information needed to assess these products?

Bottom line: indaziflam was rushed to market without careful evaluation of the numerous potential impacts of its use. The County was an early adopter (pre-2019) of this chemical despite this lack of this safety data from the EPA (or anywhere). More recent analyses indicate significant areas of potential concern. As a study entitled “The Unexplored Challenge of Indaziflam in Agroecosystems,” published in 2025, noted in its conclusion:

“Despite its effectiveness as an herbicide due to low application rates and long residual activity, indaziflam warrants serious concerns due to its likely environmental risks—particularly based on persistence, toxicity, and leaching potential.”

What we don’t know about Rejuvra/Esplanade/indaziflam’s health risks is scary. In fact, 80% of what is in the bottle is undisclosed by Bayer/Envu. Neither the EPA nor our County staff know what’s in it—and it’s not just water. And, what we do know is also scary.

Here’s what we know about indaziflam’s toxicity to non-target species:

Soil micro-organisms are affected.

Indaziflam alters the soil microbiome. A recent Boulder County study showed that both bacterial and fungal soil communities were significantly different between treated and untreated sites, including indicator species in treated soil associated with toxins. For an Open Space program that prioritizes soil health, much more rigorous scientific research on soil microbial/fungal impacts are needed before further use.

Indaziflam is directly toxic to invertebrates, fish, and aquatic plants.

EPA ecological risk assessment shows that indaziflam is toxic to fish and aquatic invertebrates. There are no studies for soil invertebrates, including soil nesting bees. The only independent studies for direct toxicity to invertebrates shows that indaziflam is found in coastal waterways and is highly toxic to clams.

There are known risks from indaziflam to human health.

EPA testing raises multiple red flags about human health risks from indaziflam.

Neurotoxicity. Indaziflam is neurotoxic. EPA tests showed decreased motor activity, clinical signs, and neuropathology.

Organ Damage. EPA testing shows organ damage to kidney, liver, thyroid, stomach, seminal vesicles, and ovaries.

Potential Endocrine Disruption. Testing showed changes in thyroid function.

Developmental Toxicity. Testing showed decreased weight in offprsing and delayed sexual maturation.

Cancer Risk. Although EPA standard tests showed no evidence of carcinogenicity, an independent 2023 study showed that another type that indaziflam caused DNA and chromosome damage, which can lead to cancer.

What about birds and other wildlife?

We just don’t know. No environmental impact assessments have been done.

What safety data does exist for these products?

Well, shoot. This isn’t looking great for indaziflam. It’s too bad there are no non-chemical alternatives to reduce non-native plants and restore biodiversity to our public lands.

Finally, we get to some good—no, GREAT news!

A growing body of local expertise from restoration ecologists and regenerative land stewards proves that there are multiple non-chemical management options for species like cheatgrass, which, again, are fully naturalized and will never be completely removed from our landscapes.

There are viable grazing-based control approaches. County Staff publicly dismissed cattle grazing as a viable practice in the Red Hill drone treatment area because they said there was no fencing in the area. However, this dismissal appears to overlook or ignore a range of emerging grazing strategies that could both address the barriers noted by staff and provide a wide range of co-benefits. This includes a whole new generation of grazing management strategies that use either low-impact mobile fencing systems or new radio collar herd management systems that can pinpoint grazing as a weed control function timed with the emergence of cheatgrass in the spring. While the costs of these treatments would be significantly higher than drone-based applications of a chemical, they would also not have any of the non-target impacts that have enormous long-term ecological and human health costs.

Several experienced local grazing managers have expressed interest in a pilot project on Red Hill to demonstrate and monitor these approaches. There have also been local investors expressing interest in a public-private partnership to co-invest in research on such an approach. Such an approach should be given at least a 2-3 years pilot with treatments at the scale of roughly the size of the Red Hill area (~300 acres) to evaluate both short and longer term efficacy, cost, and impacts.

Importantly, we have time to try non-chemical alternatives!

Cheatgrass has been naturalized in our area since the 1800’s and there is no urgent threat to the areas currently targeted for drone treatments that are going to change dramatically over the duration of a 2-3 year pilot project. The push for large scale drone treatments is based on a false urgency that is not justified given the enormous potential social and ecological impacts of this highly toxic and potentially dangerous chemical treatment strategy.